By Bobby Gonzales

Marissa Perel is a Brooklyn-based artist, writer and curator whose projects span the worlds of art, music, and dance. She is the 2013 curatorial fellow at AUX, the Philadelphia performance space, where she has organized performance events and lectured on her work. In Fall, 2013, Vox Populi member Bobby Gonzales spoke to Perel about her time at AUX and her own artistic ventures.

Performance by Eileen Doyle. Photo: Sharon Koelblinger.

Bobby Gonzales: You are Aux’s inaugural curatorial fellow. Your practice seems ideal for the openness of the position. Can you talk a little bit about how curating, specifically for AUX, might feed into your practice as a performer or as a writer?

Marissa Perel: I think of curating as world-building. It’s not just the work, but how the work activates the space, and the context of the space, and the people in it. I’m also seeking to do that with language in writing and artistic practice. I want the work I make and do to facilitate new ways of seeing and understanding art, each other, the world around us.

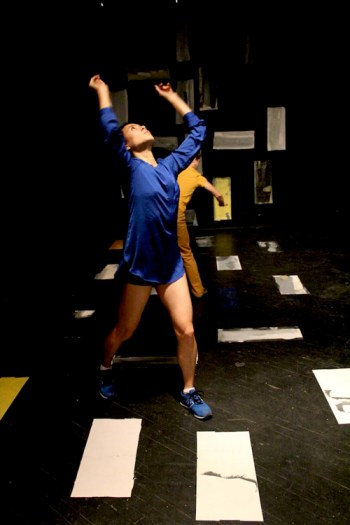

Performance by iele paloumpis. Performed by Joanna Groom and iele paloumpis. Photo: Sharon Koelblinger.

BG: I’m interested in artists who write. I feel personally like I need to write in order to think. How does writing function for you? Did you write a lot while developing ideas for curating at AUX? Do you build the worlds with language first, and bodies second?

MP: It’s funny you should ask me this because I actually had a revelation about the programming I’m doing last night, and I sat down and wrote it out as soon as I got back from the bar after the show. I finally figured out the overarching concept from seeing the fruition of my initial programming. But I think if you look at my writing on-line and read my articles and interviews, my interests are very public. As an artist, writing is fundamental to my practice. It’s how I figure out what I’m doing in the studio and how I translate or transform material into performance.

BG: Well, what did you figure out last night? Divulge!

MP: One interesting thing about the through-line of the work I’m curating is that most of the artists are queer. Queerness is part of their compositional models. This speaks to some idea of “queer futurity” in the world of art and the world at large that I am seeking to envision: how politics and aesthetics become historically intertwined and lead to conscious and unconscious choices, desires, and modes of production. What is collective, what is selective, where is there rebellion from or fusion with historical precedence of queerness? Can these patterns be traced in the work or are they simply personal? I’m thinking about queerness not only as related to sexuality and gender identity, but including many forms of variance and difference.

“This room this braid, part 1,” choreographed by devynn emory, performed by devynn emory and Aretha Aoki. Photo: Lindsay Browning.

Bobby: The way you use the space and curate events in it has been really eye opening. There isn’t one set way to shape the space.

Marissa: Working with space in site-specific ways, even if the space is a theater, is for me the product of years of performing and curating at communal spaces where the body is at the center of the work. It’s the performer who activates the space and dictates the audience’s attention. You don’t necessarily have to stick to a typical front and back of house, and a performance doesn’t have to have a linear start and end. Part of what has influenced me is taking Contact Improvisation classes earlier in my life, where you’re observing in order to participate. You watch another person’s body in order to learn how to dance with them. In that practice you lose track of time and space because collective movement and energy shape the piece. An evening length piece, for instance, can be something where the audience comes in and then leaves, is asked to participate, is left in the dark, or where the end comes first. Time is the medium. I’m thinking of Chris Burden’s “Shout Piece,” where as soon as the audience entered the gallery he shouted, “Get the fuck out,” through a megaphone with his face painted red.

“Three Frames,” choreographed by Sandra parker, performed by Ben Asriel. Photo: Bobby Gonzalez.

Bobby: Experiencing that kind of permission is something new for Philly audiences: being allowed to walk around a performer or choose where to sit to view a performance.

Marissa: I don’t think perception is ever fixed, not even in visual art. Your experience of an object changes each time you view it. I don’t like the idea of performance being fixed, where you have to watch the thing happening in front of you, and if you don’t like it, it means you don’t get it. Being allowed to leave and come back or actually challenge what you’re seeing might change how you perceive the performance. I think of what I’m doing at AUX as carving out landscapes within and around the space.

Performance by iele paloumpis. Photo: Sharon Koelblinger.

BG: Your first event at AUX, “Subject Worthy: The Wounded Body in Performance” explored “pain, embodiment, and resistance” in relation to performance. Having chatted a bit with you before about your background, I know that you’ve had some pretty traumatic experiences with pain and injury. How did the recovery from your accident influence how you think about endurance and the durational aspects of performing for an audience?

MP: Lying still for a long time takes a lot of patience. Time stretches out and you get taken out of the normal day-to-day life cycle. You have to have a lot of inner strength to endure that level of stillness, and the feeling of time passing you by. This is also in combination with experiencing pain and eventually realizing that it will never be resolved. So you have to reconcile enduring that with living your life the best way you know how. I developed a talent for receptivity, high levels of sensitivity and perception of my environment, and a felt sense of spaces. I also dropped a level of self-consciousness or judgment of myself and started using my body, because I needed to start a process of redefining my relationship to it. I didn’t care whether people valued it or not when I started.

BG: I’m going to try and ask you this without it being a leading question: Is there anything to be said about queerness, and it’s relationship to what you just spoke about?

MP: Yes, definitely. On one hand I was struggling with disability, being othered in a new way. I have a hard time with that label because I feel like an exception in terms of what I’m able to do. But at the same time, I became really removed from gender identity. When you’re a patient or subject for most of the day, it’s hard to return to any kind of normative meaning. In my adult life, I always felt like gender identity was another layer of being that I struggled to access. My values formed around something else, something more transient and elusive than a static ideal of attributes.

BG: You’ve been in Philly since the beginning of September doing the residency. Just before our meeting today, you had your laptop and cellphone stolen. There is a lot that could be said about the grit of this city. What is your impression of it?

MP: There are some creepers who walk around the 319 building, and I guess I’m not immune. I’ve actually seen a lot of violent things happen since I’ve been here, though I’ve never been in danger. It reminds me of early experiences I had living in Brooklyn. There isn’t a fake sheen on anything here. Poverty, addiction, class and race tensions are apparent.

“This room this braid, part 1,” choreographed by devynn emory, performed by devynn emory and Aretha Aoki. Photo: Lindsay Browning.

BG: What is next for you? Does your experience here factor in?

MP: I think it is going to be a hard transition to return to New York after meeting so many amazing artists and people in Philly, working with them, and finally finding a way into people’s worlds here. After the 10 or so events I’ll have produced at AUX, and living in Philly for 4 months, my outlook will be highly influenced by this place. I’ll be returning to writing, editing, and independent curating, but perhaps with a new frame of mind. In January, I’m performing at the Poetry Project Marathon Reading at St. Mark’s Church in New York with Philadelphia musician Chris Forsyth. In February, I’ll be touring Europe with Drummers Corpse, a twelve-piece drum band headed up by Mike Pride. I’ve been working on a performance-installation that will open next year at The Chocolate Factory Theater in New York.